The famous tunnel bust-up between Patrick Vieira and Roy Keane from February 2005 is often used to highlight the classic rivalry between Arsenal and Manchester United. But that match came after the period when those two were the Premier League’s dominant sides. United’s 4-2 win took them up to second, but they were still eight points off the top, with Arsenal another two points behind leaders Chelsea, who had a game in hand. But Jose Mourinho’s side didn’t excite most neutrals, so Arsenal versus Manchester United was still the biggest show in town.

This season’s Premier League title is far from sewn up — Arsenal are six points clear with 13 games to go — but there was a similar sense at Anfield on Sunday that, despite Manchester City’s clashes with Liverpool no longer being title deciders, this remains the Premier League’s must-see fixture.

Whereas these two sides’ three matches against Arsenal this season have produced a total of three goals, this contest produced three in the final 20 minutes. Their rivalry can be summarised by the ludicrous mutual fouling between Erling Haaland and Dominik Szoboszlai that ultimately ended with a disallowed ‘goal’ from the halfway line: two giants battling it out, trading blows, but happy to shake hands afterwards.

Erling Haaland and Dominik Szoboszlai battle desperately in the game’s final twist (Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images)

The action happened completely separately from the tactical battle.

For 70 minutes, this was a tense, engaging contest where both managers did interesting things. Pep Guardiola used a narrow system and his Manchester City side constantly found an extra man in midfield to slip through balls in behind Liverpool’s defence, including when Haaland had a decent chance in the very first minute. Liverpool rotated the positions of their attackers well to open up passing lanes and create chances — both Florian Wirtz and Hugo Ekitike should have done better from presentable chances. For once this season, this was a big Premier League game based around quality in open play. And yet, all that was still largely irrelevant to the scoreline.

Instead, the goals came from a cracking long-range Szoboszlai free kick, a smart Bernardo Silva finish from a Haaland knockdown, which felt like a big man-little man combination from the 1990s, and then a Haaland winner from the penalty spot after Alisson, the league’s most reliable goalkeeper in recent years, dived into a situation unnecessarily. OK, you wouldn’t necessarily consider any of the goals as being ‘against the run of play’, but none of the incidents really stemmed from what either side was actually trying to do.

Erling Haaland’s penalty gave City a rare three points at Anfield (Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images)

This is the thing about this season’s Premier League: it’s difficult to draw a direct line between the managers’ tactical decisions and the outcome of matches.

Only a few years ago, this felt relatively straightforward. Contests were about gaining the upper hand in midfield, or getting a certain player into space, or dominating one zone on the pitch. Elsewhere, that is still the case. The day’s big game in the Women’s Super League, for example, was decided by the presence of one player, who came into the side with one specific task. She did it perfectly for the only goal in a 1-0 win.

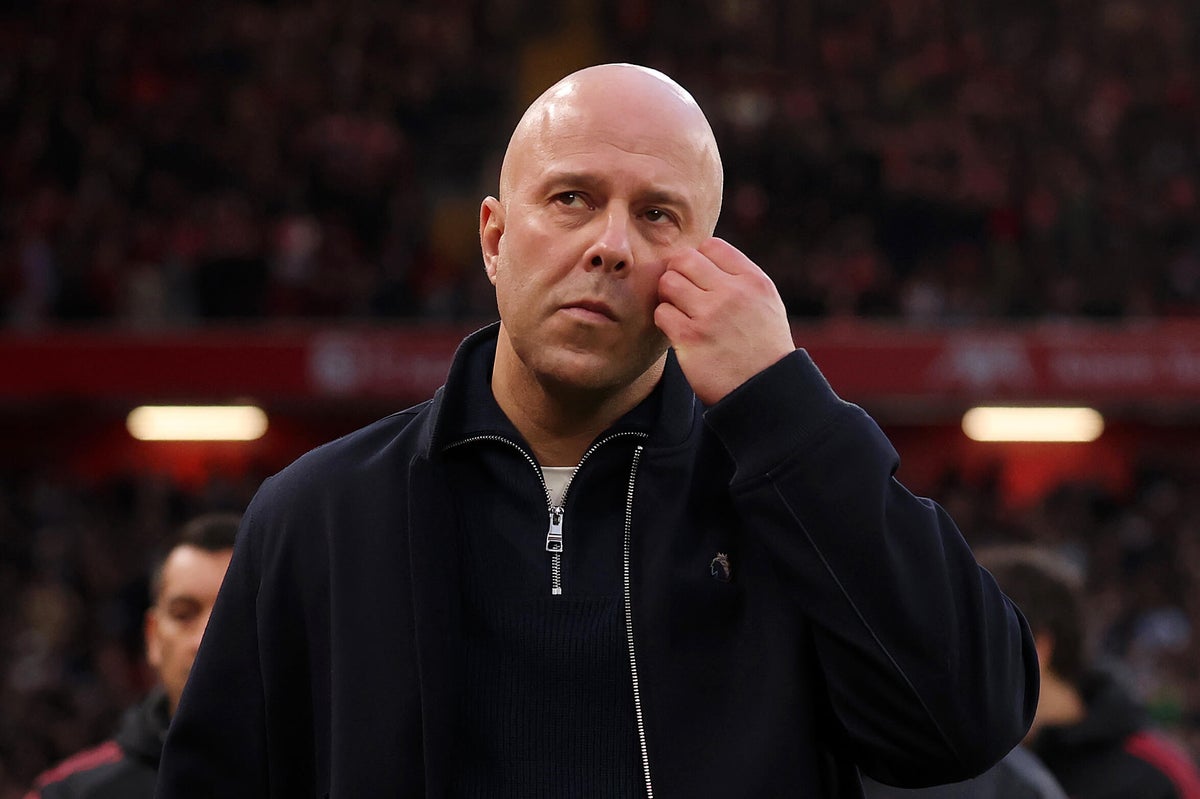

But Premier League games are so frantic, so based around duels, man-marking and individual decision-making, that it feels increasingly like managers have no control whatsoever. That is true even of Guardiola, the ultimate control freak. And it’s certainly true of Arne Slot’s Liverpool.

Last season, Liverpool won a couple of matches in ‘boring’ fashion, going 2-0 up and then killing the game by sitting back and defending, or keeping possession at a low tempo, and some missed their back-and-forth style previously seen under Jurgen Klopp. Equally, there was some acknowledgement that Klopp’s Liverpool had fallen short the previous season precisely because they couldn’t apply the handbrake.

This season’s Liverpool are more up-and-down. Milos Kerkez is all about overlapping from left-back. Szoboszlai is a No 10 converted into a right-back. Wirtz has made the midfield more attack-minded. When combined with the frenzy of Premier League matches and home supporters’ intense demands to capitalise on momentum by going for more goals, Liverpool often can’t slow down the play.

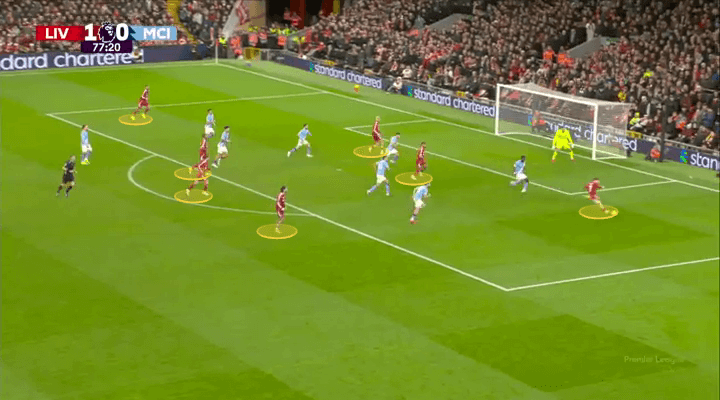

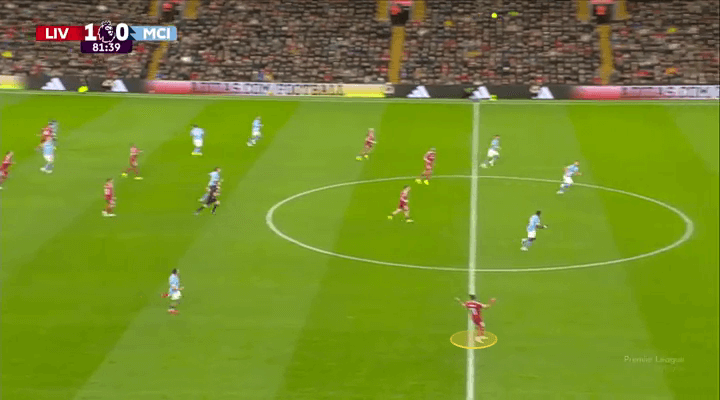

During the 10 minutes when they were in front yesterday, Liverpool made no attempt to retain possession and slow the tempo. There were no examples of time wasting. Slot didn’t make any substitutions to bolster the midfield, and carried on using four attackers. And so Liverpool ended up in some mad situations. At 1-0 up, do they really need seven men in and around the box here?

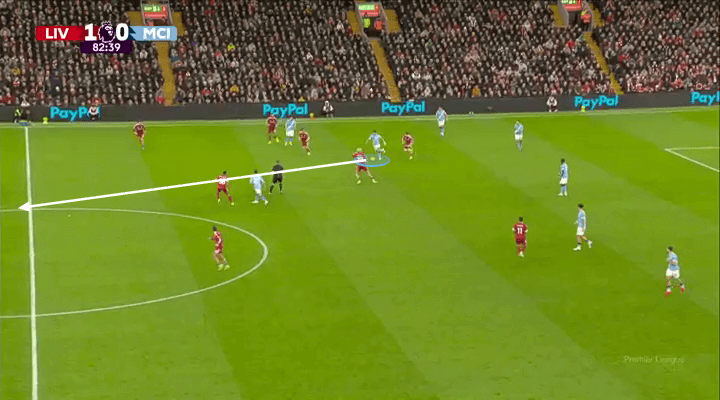

Is it acceptable for Kerkez to aimlessly smash this ball downfield and hand possession back to City? Not according to a visibly frustrated Mohamed Salah.

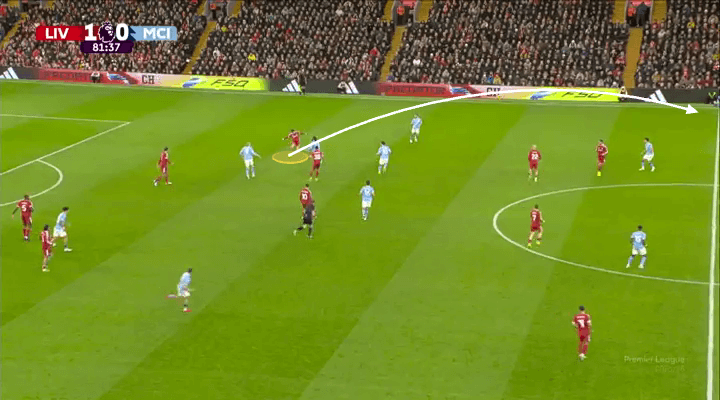

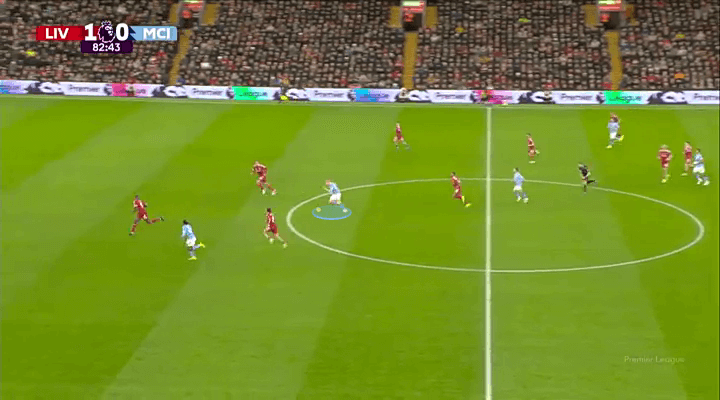

Is it reasonable that Liverpool can be open enough for City to prod a pass through their midfield and into the Premier League’s most dangerous striker, who can turn and run at goal?

For the neutral, there is much to admire about all this. The game was so enjoyable because of both sides’ ambition. But sometimes this crosses into naivety, and Liverpool seem completely unable to read a game.

The bizarre incident at Bournemouth, when they spent five minutes happily playing with 10 men rather than putting the ball out so a substitute could be introduced, sums it up. Liverpool just want to play. They don’t want to think.

Their concession against Newcastle last weekend was followed by Virgil van Dijk screaming to his team-mates that they were “too open”. Alisson’s mistake for City’s penalty felt similar to when Ibrahima Konate senselessly dived into a challenge away at Leeds United and conceded a penalty: Liverpool had been 2-0 up and cruising to victory and ended up drawing. Liverpool’s shape is looking less structured, and their defensive players frequently make rash decisions.

Slipping to a last-minute defeat against a team who have won four of the past five Premier League titles is forgivable, but the most damning aspect of Liverpool’s season is their record against the promoted sides: played five and won only one, courtesy of a last-minute penalty at Burnley.

On Wednesday, they play their sixth and final match against that trio, with a trip to a Sunderland side who sometimes lack invention, but who sit deep and are tactically disciplined. For Liverpool at the moment, that is a recipe for disaster.